The most popular Spanish artist to hit American in the early seventies was the talented, Esteban Maroto. Born in Madrid in 1942, he began his comic art career serving as an apprentice to Manuel Lopez Blanco in the early sixties. The young artist's first efforts focused mainly on the various romance comics of the time. But before long, Maroto advanced into the adventure, fantasy, and science fiction realms working with his close friends, Carlos Gimenez and Garcia Pizarro, on the Buck John and Merlo the Magician features. Though once Maroto joined the influential Barcelona art agency, Selecciones Illustrada, his tremendous skill as a draftsman and illustrator really began to flourish. Three well drawn strips, Alex, The Beat Group, and Amargo, quickly caught on with the fans due mainly to its collection of beautiful women characters. Maroto's reputation for drawing the female figure quickly made him the most sought after romance artist, especially in England. But his real breakthrough was with the strip Five for Infinity which helped clarify his unique ultra-detailed style. Always lush and decorative, his pages had a hard linear look, similar to his earlier works, but now with an appealing large scale composition. While working at the art agency, Esteban also contributed to the German feature, Roy Tiger, and created his two best known fantasy adventures, Manly, and Tomb of the Gods.

In 1971, an exciting event occurred when

Buru Lan created the New English Library and published its first

Dracula magazine in brilliant color. Though the

oversized periodical was short on pages, it was long on new talent, with the works by

Maroto,

Sio, Enrich, Bea,

Solsona, and other dedicated horror/fantasy artists.

Maroto created an exciting sword-and-sorcery feature

Wolff for this magazine’s all too brief, twelve issue run. This new horror periodical, published in both Spain and Britain, quickly made a big impact on the general public, as well as one American publisher, Jim Warren. Soon

Maroto and his other talented

Selecciones Illustrada peers were being showcased in the extremely popular black-and-white Warren magazines,

Eerie,

Creepy, and

Vampirella. It is thought by many that this was

Maroto's "peak period" of his long and

distinguished career, producing some of his finest works. Finding inspiration from his earlier barbarian tales, Esteban added more fresh experimental approaches to his drawings. His first story for Warren was the beautifully rendered Wolf Hunt, which appeared in

Vampirella #14. The artist’s moody detailed pages with their beautiful women and highly textured backgrounds were an immediate hit with the American magazine's male fan base.

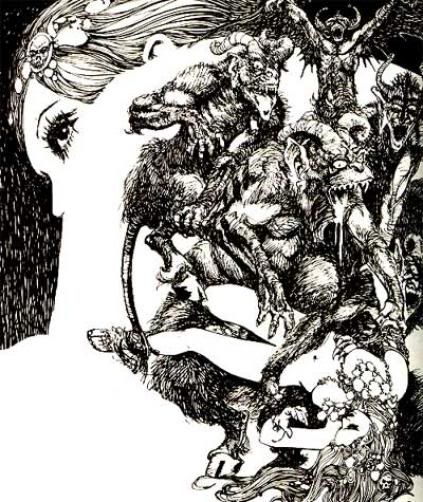

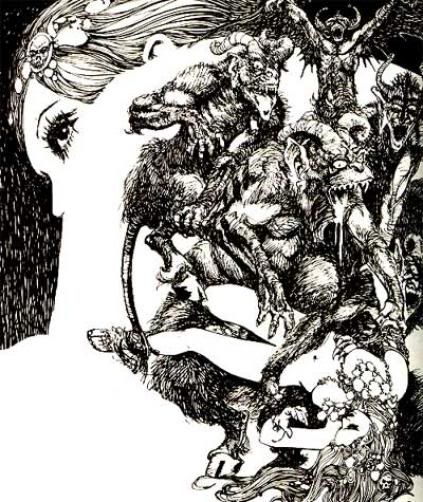

One of Maroto’s special artistic abilities was to draw each page as a whole composition, ignoring panel limitations in favor of combining images into one complete baroque composition. Esteban used all the greatest elements of both his earlier Manly and Wolff strips as a model for Warren's new fantasy creation Dax the Warrior, which debuted in Eerie #39. The artist knew by now what his fan base wanted, and never failed to provide them with a strong dose of sex appeal and barbarian fantasy in his elegant immaculately drawn style. Dax the Warrior had only twelve stories, that averaged a mere eight pages each, but they were always packed with lovely distressed women, horrible seething monsters, an evil wizard or witch, all cleverly reworked as mythological tales, with our fearless lithe hero, Dax.

Some stories were criticized proclaiming

Maroto could not write a good fantasy tale. However, I never had a problem with his writing, because the real appeal for these few artistic gems was the combination of sword, sorcery, and sex appeal.

Maroto drew almost one-hundred stories over his twelve year affiliation with Warren, but by the end, the artist's early zest for experimentation had waned somewhat, which is seen in his

linework losing some of its finesse for a more hurried scratched look. But the

Dax stories were always considered to be his favorite work and a collection of ten stories were later reprinted with new dialogue by Bud Lewis for

Eerie #56. They proved to be some interesting contrasts from the original scripts, but enjoyable all the same.

The artist also worked for Marvel Comics illustrating their black-and-white books on characters such as Conan, designing Red Sonja's chain-mail costume, and revamping Dracula's daughter,

Satana, while completing other various horror and fantasy tales. Over the years, while concentrating on his illustration work he did

numerous portfolios, paperback covers, and spot illustrations for Spanish and American science fiction magazines that were later

collected in a series of books. In the early nineties,

Maroto returned to comics working with DC on

Zatana,

Aquaman,

Amethyst, and

The Atlantis Chronicles, before contracting with

Topps , other

Italian publishers, and and his latest

Red Sonja covers for Dynamite Comics.